Celebrating World Water Day with an Adventure in Alberta

We're still processing our awesome adventure in Alberta around World Water Day. 😮💨

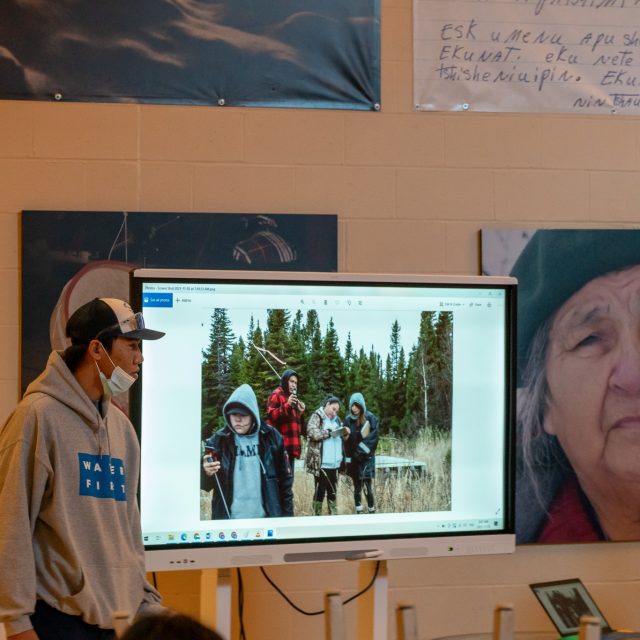

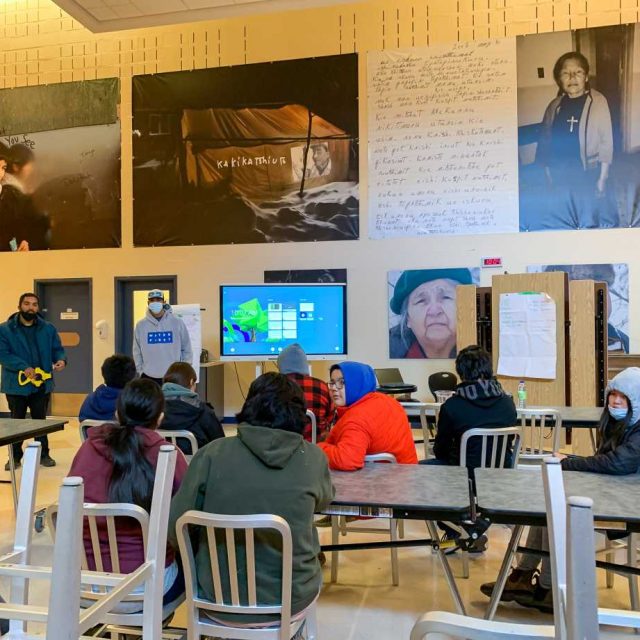

In March 2024, four departments at Water First came together in Alberta for two weeks to help strengthen relationships out west, to deliver water science programming to students, and to celebrate World Water Day!

Too many amazing moments happened during this trip to be able to share them all in detail, so enjoy some of the highlights.

From the rooftop of the venue hosting the Alberta Water and Wastewater Operator Association‘s Women of Water event, a very special group pic of people from four different Water First departments working together!

Witnessing beautiful tributes to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S), dance competitions and tons of handmade artwork at the Aboriginal Friendship Centre of Calgary‘s Red Dress Traditional Powwow.

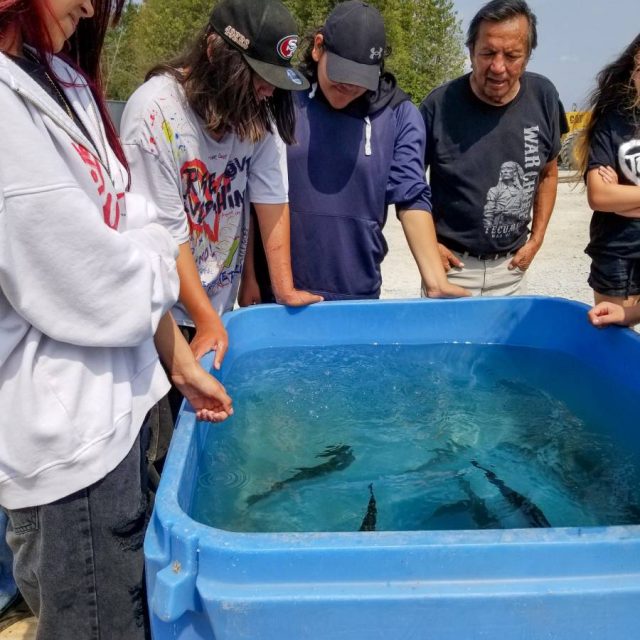

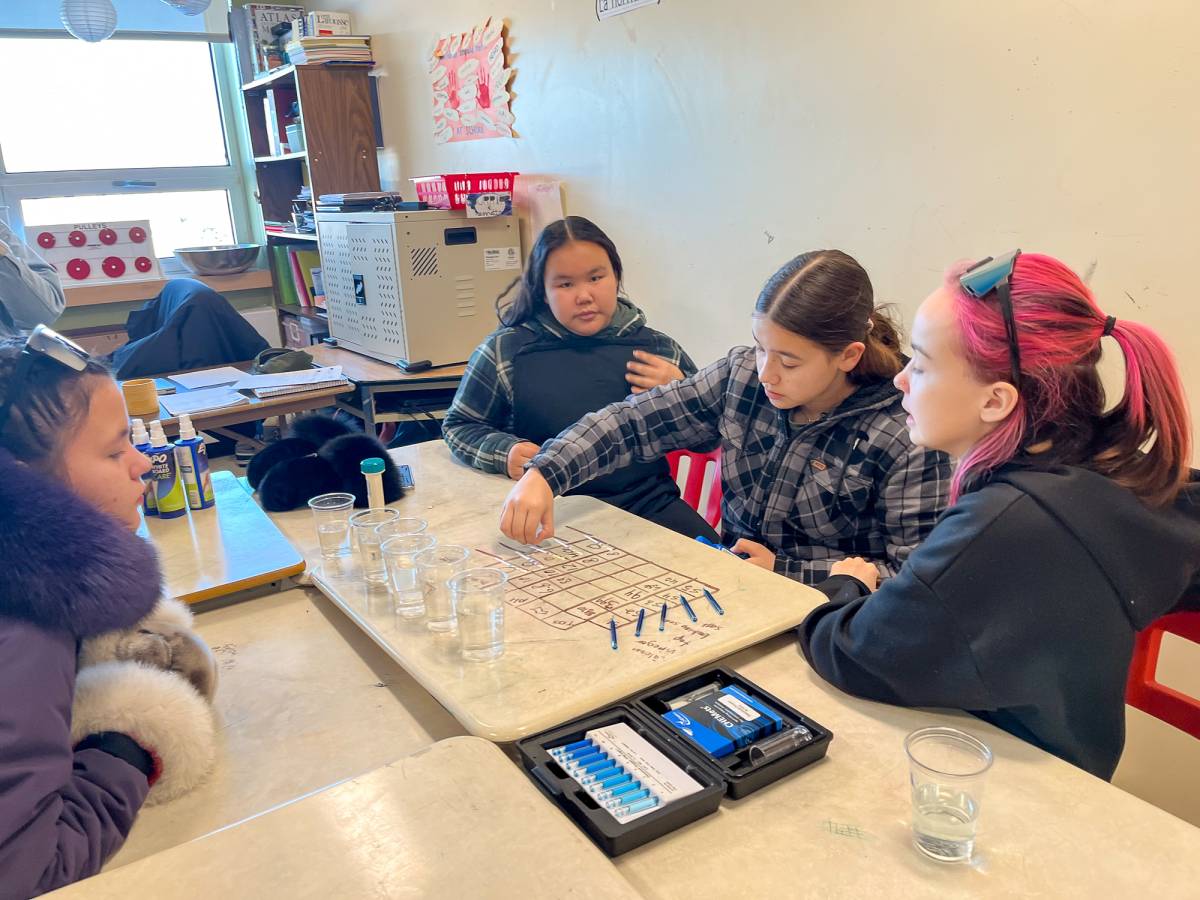

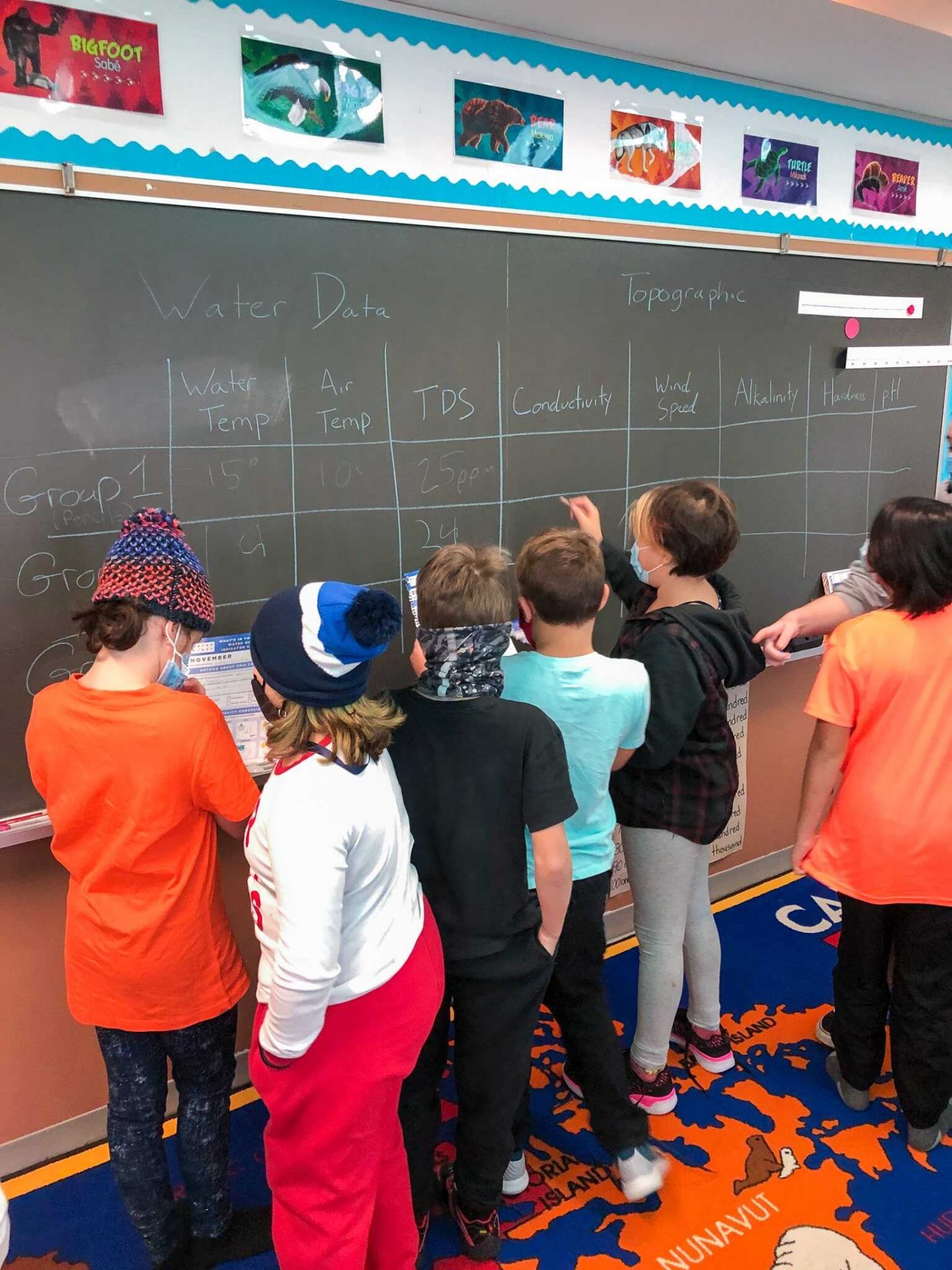

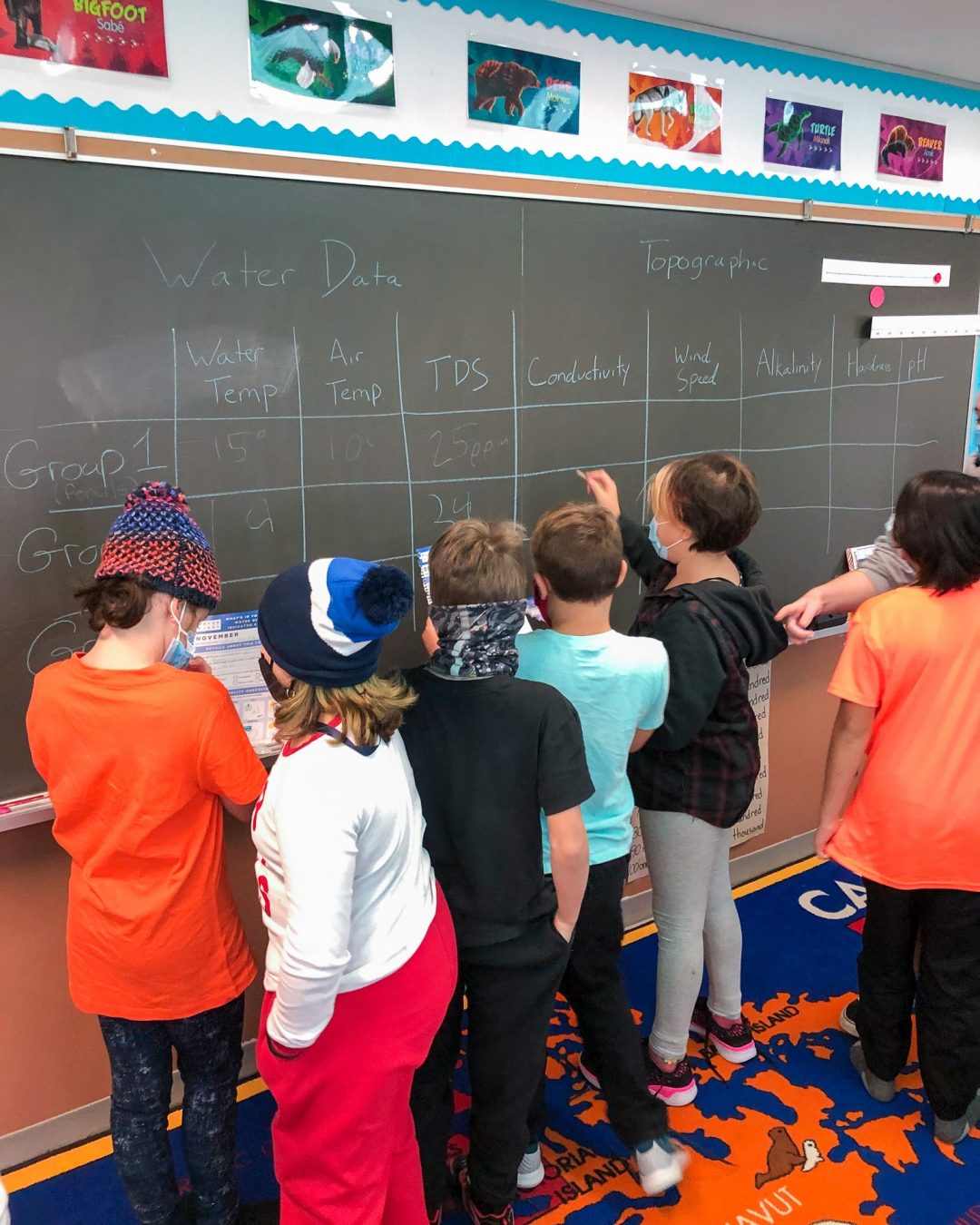

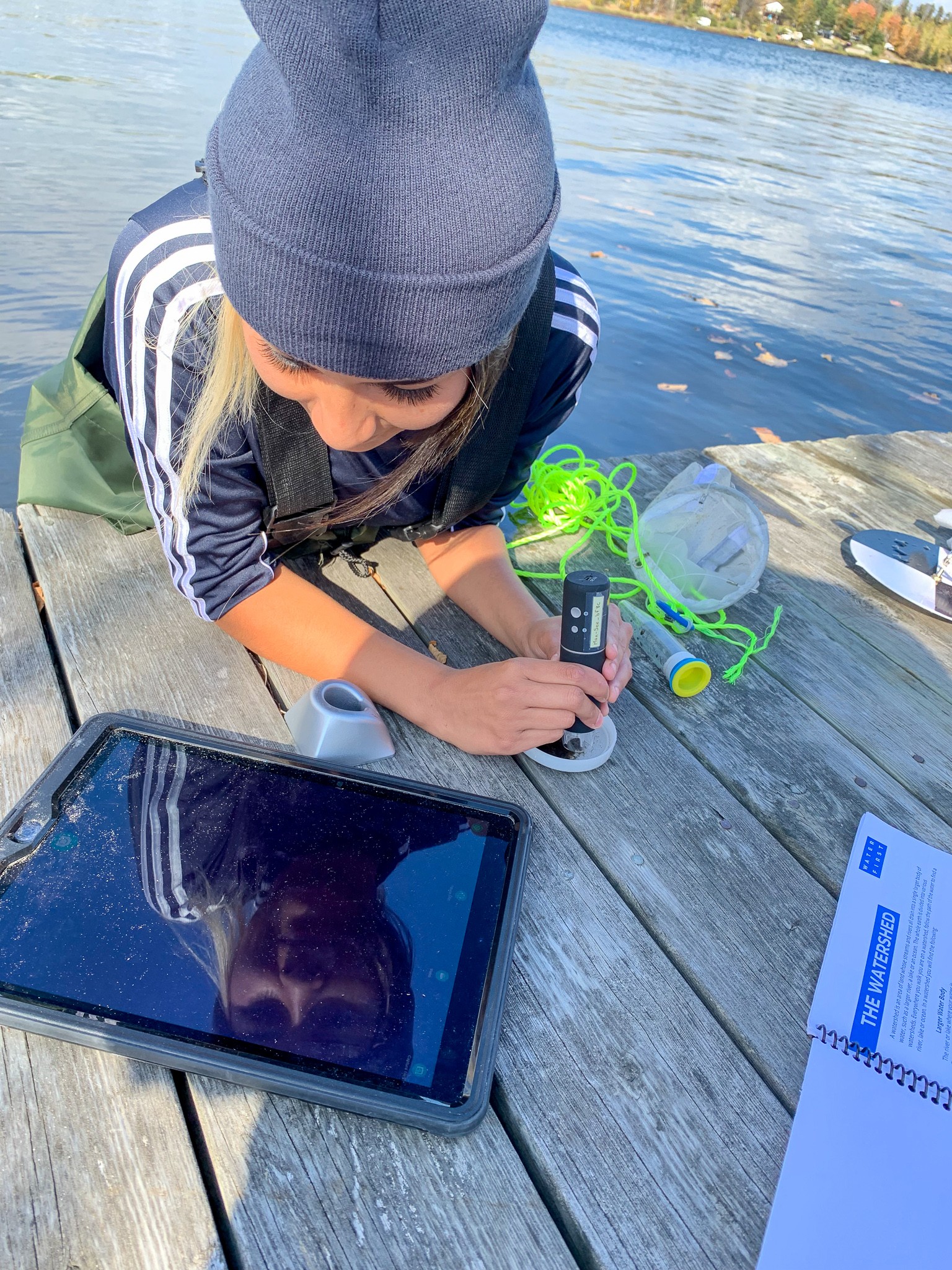

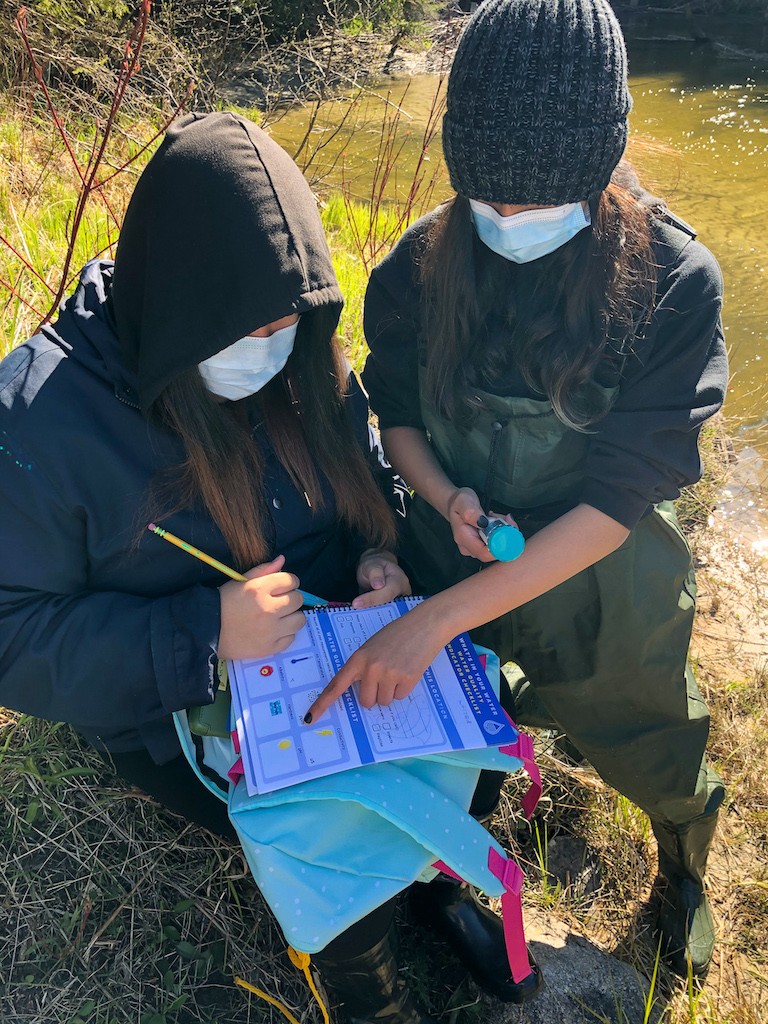

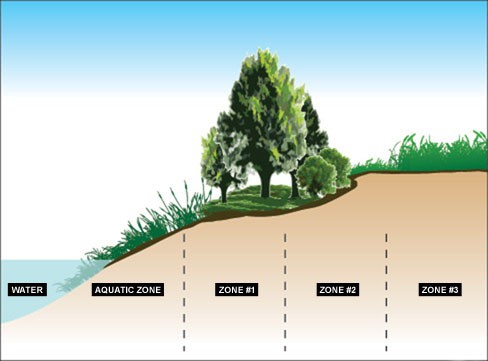

On the frozen Bow River, students from Mînî Thnî Community School put the skills they learned earlier in the week to the test as they collect water through a hole in the ice to measure different water quality parameters.

Anemometers being used to measure wind speed (and also, apparently, how many km/h students can blow 🌬️).

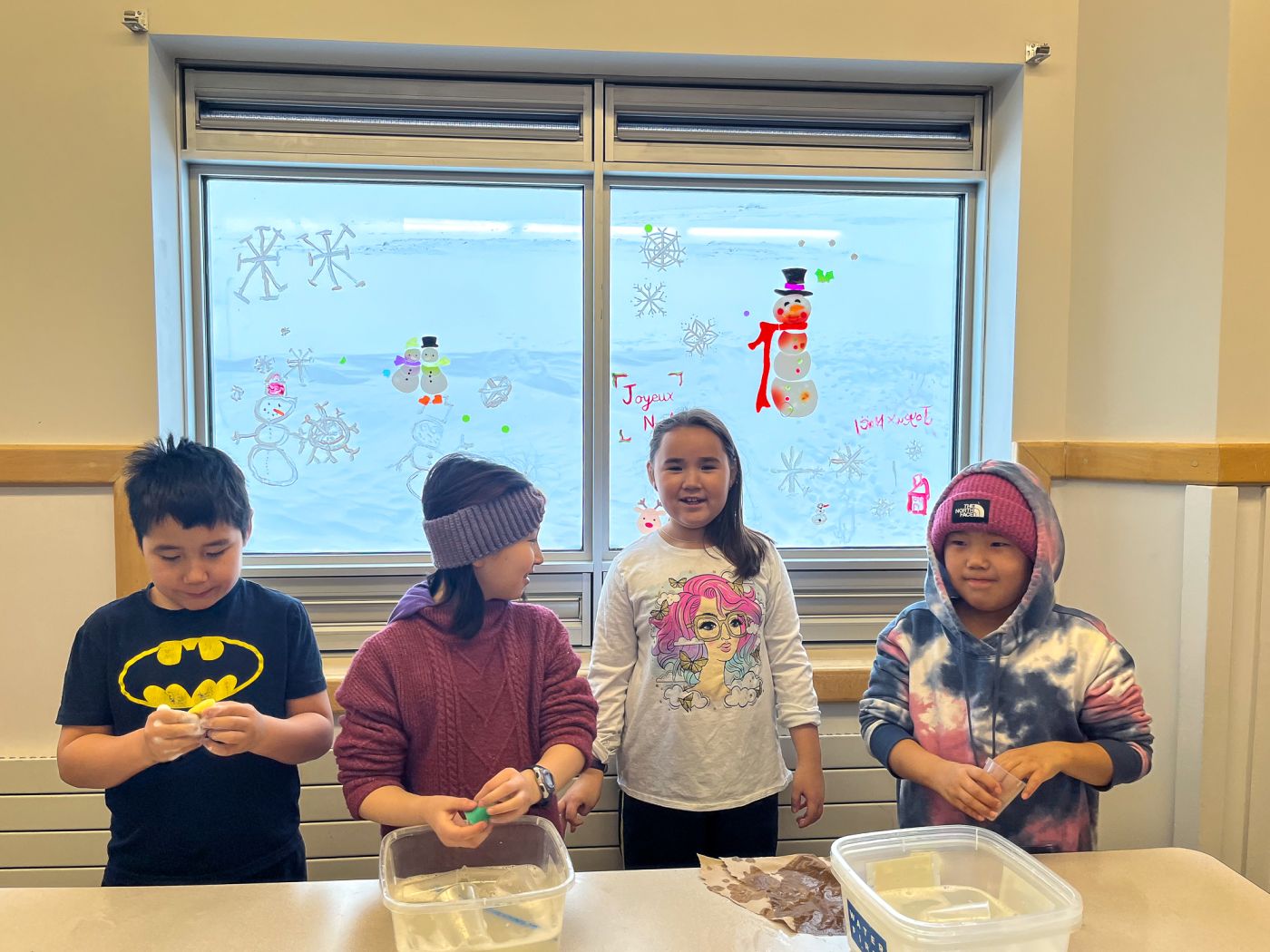

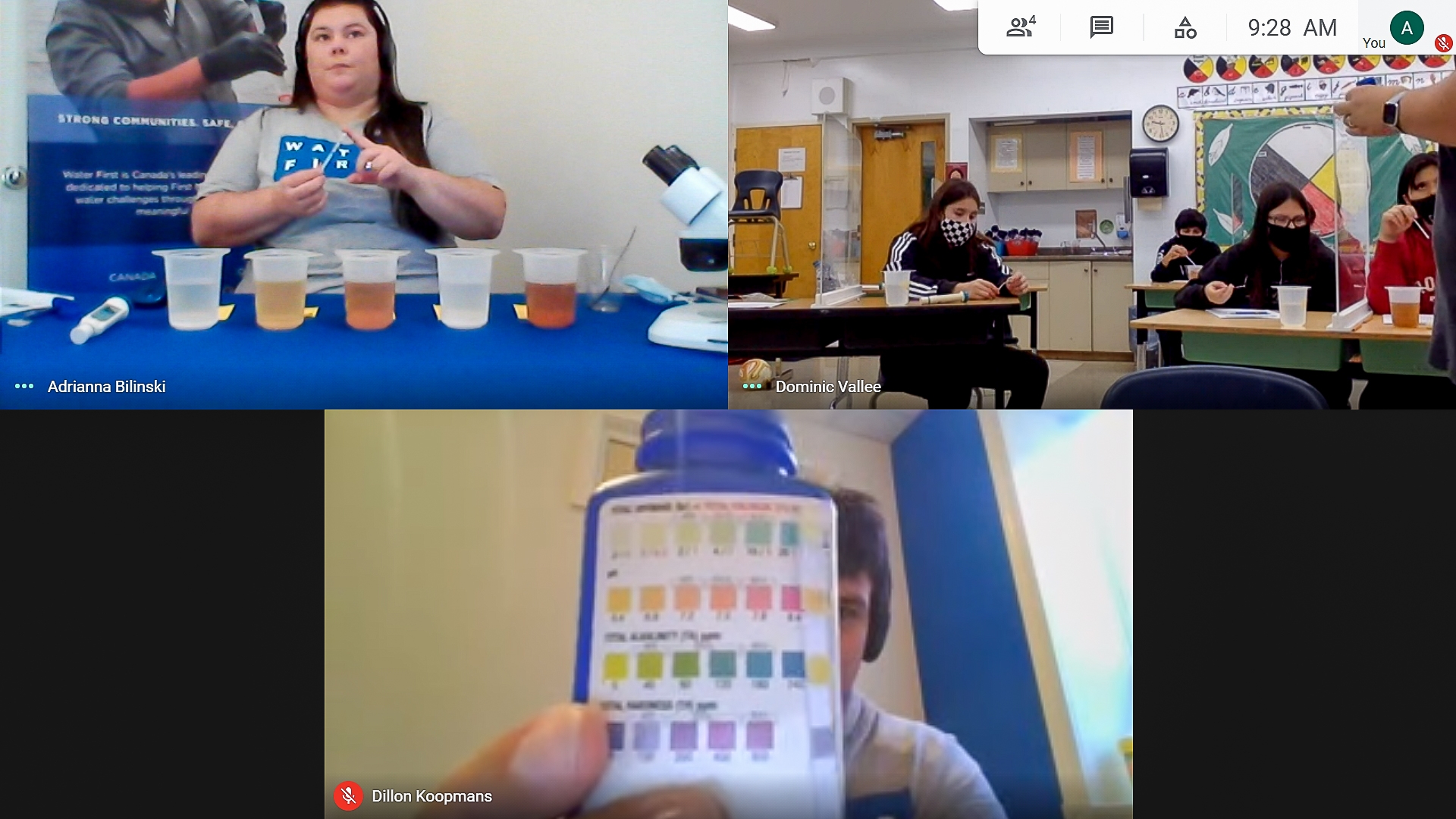

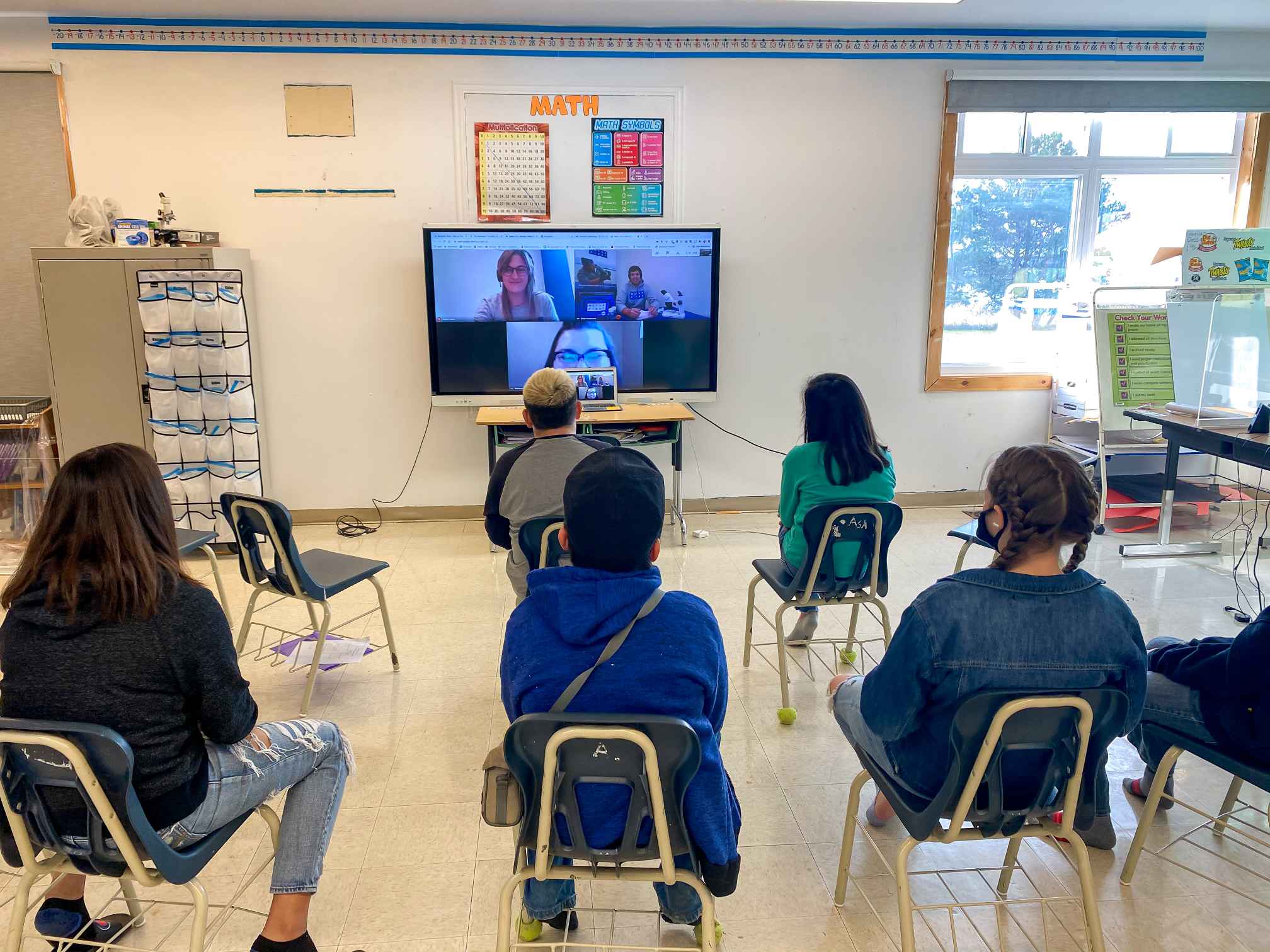

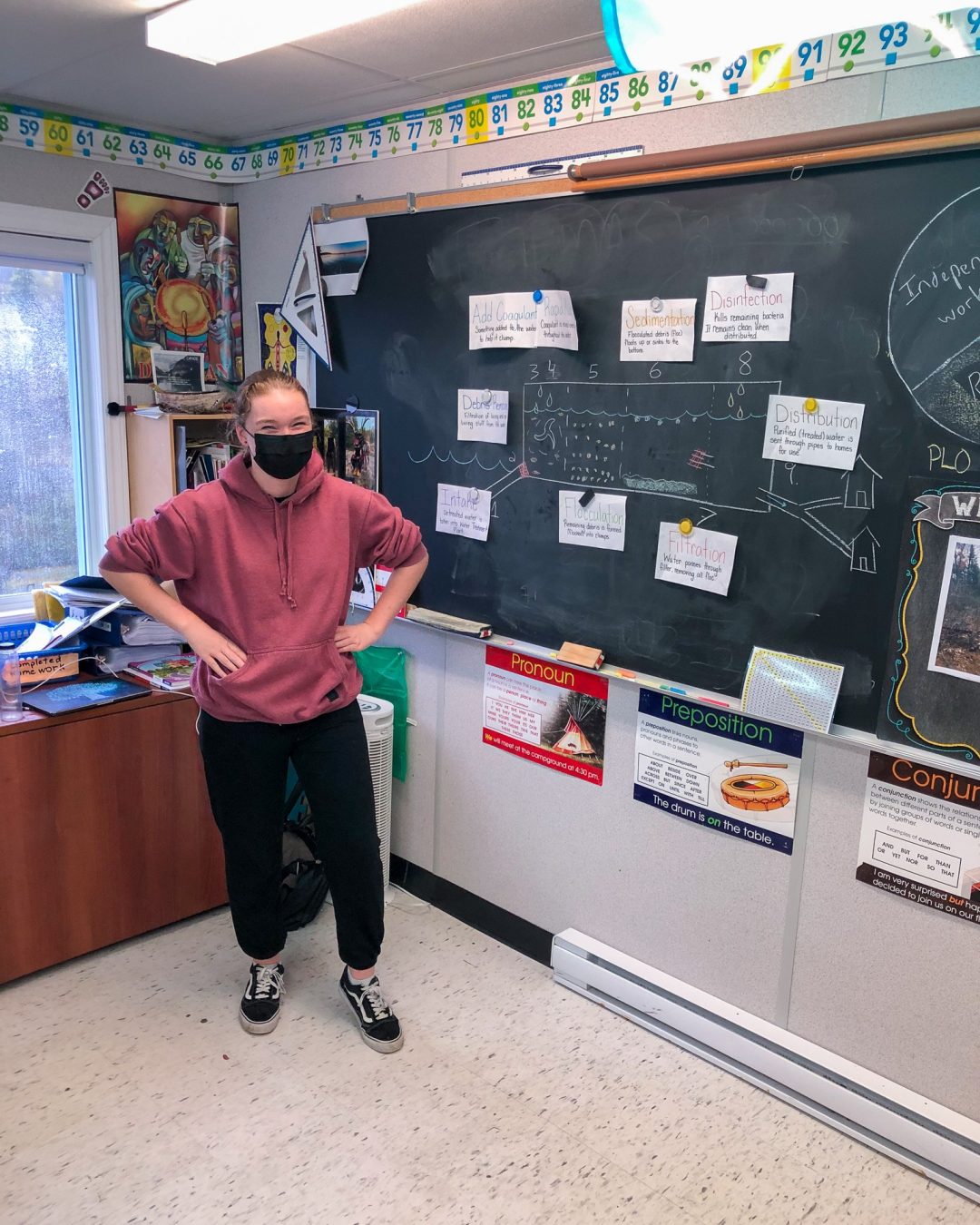

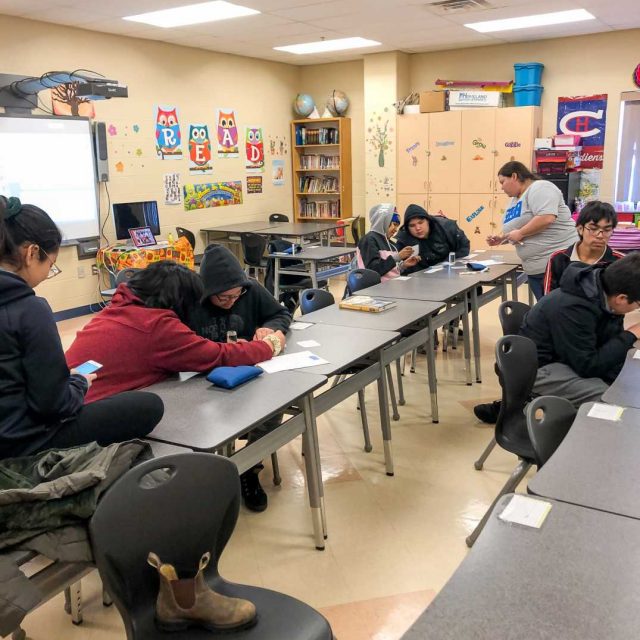

The students at Clarence Sansom School in Calgary weren’t quite as excited as Adrianna about the 10cm of snow that fell overnight, but they were definitely excited for a week of water science workshops!

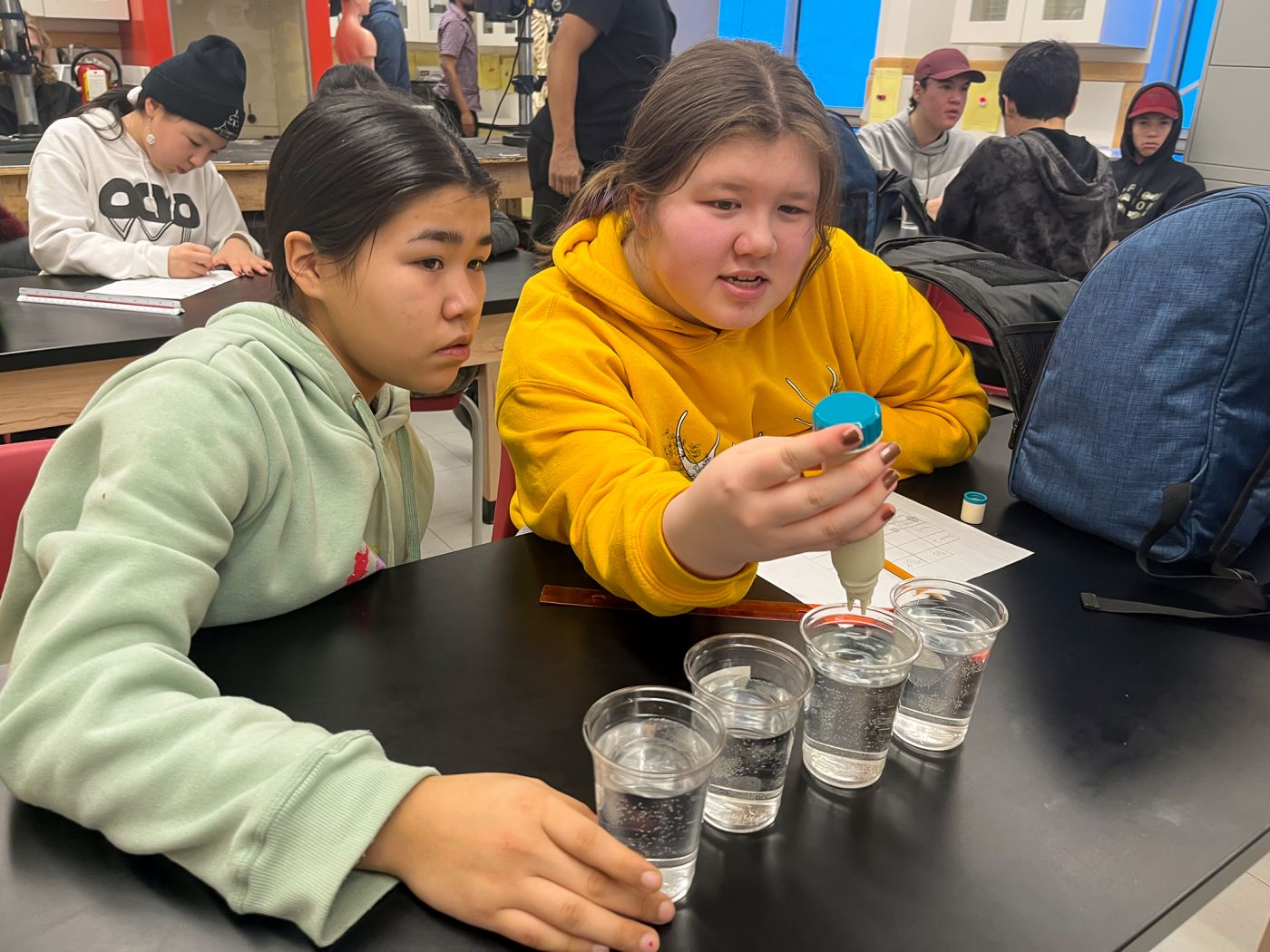

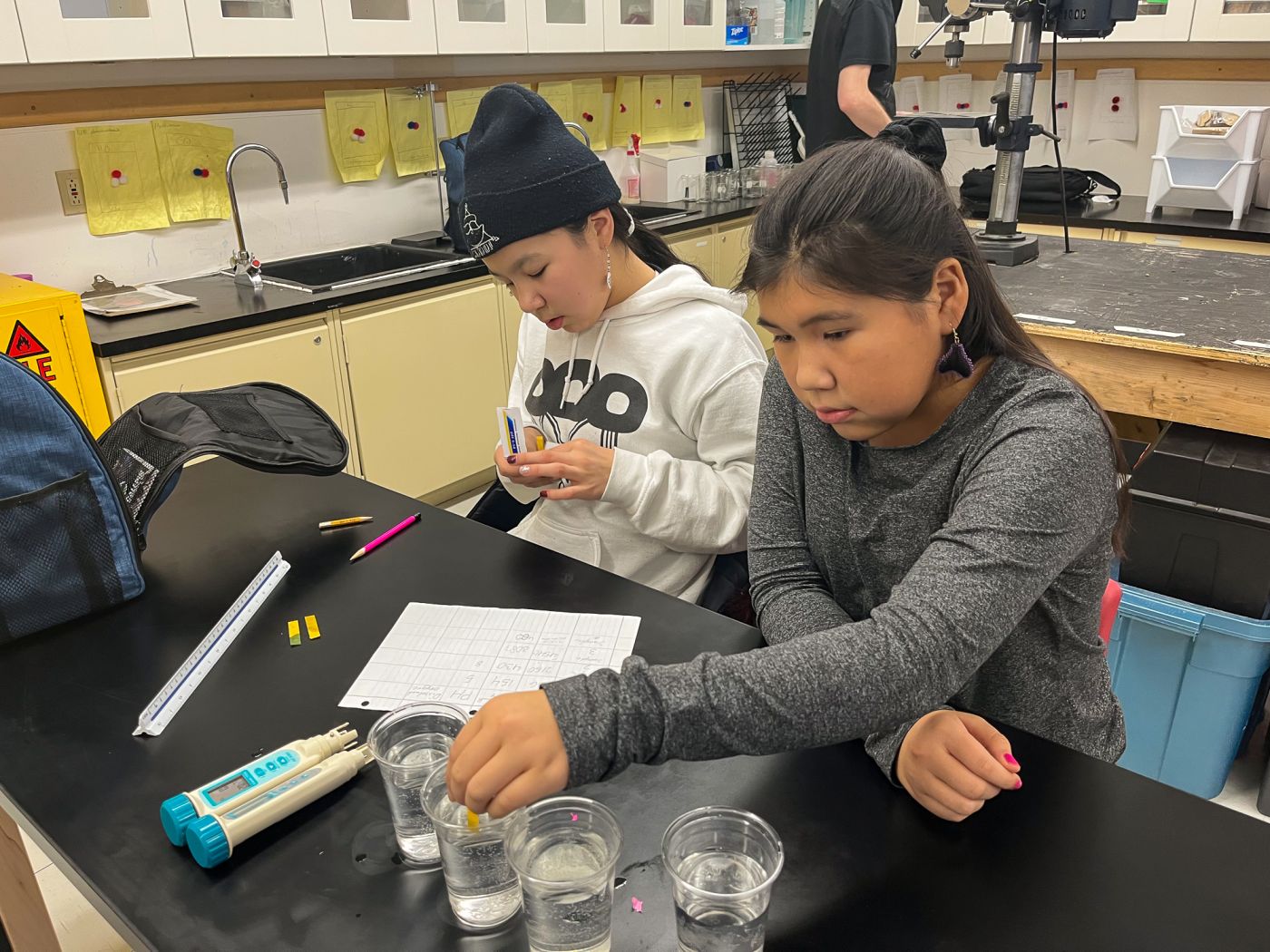

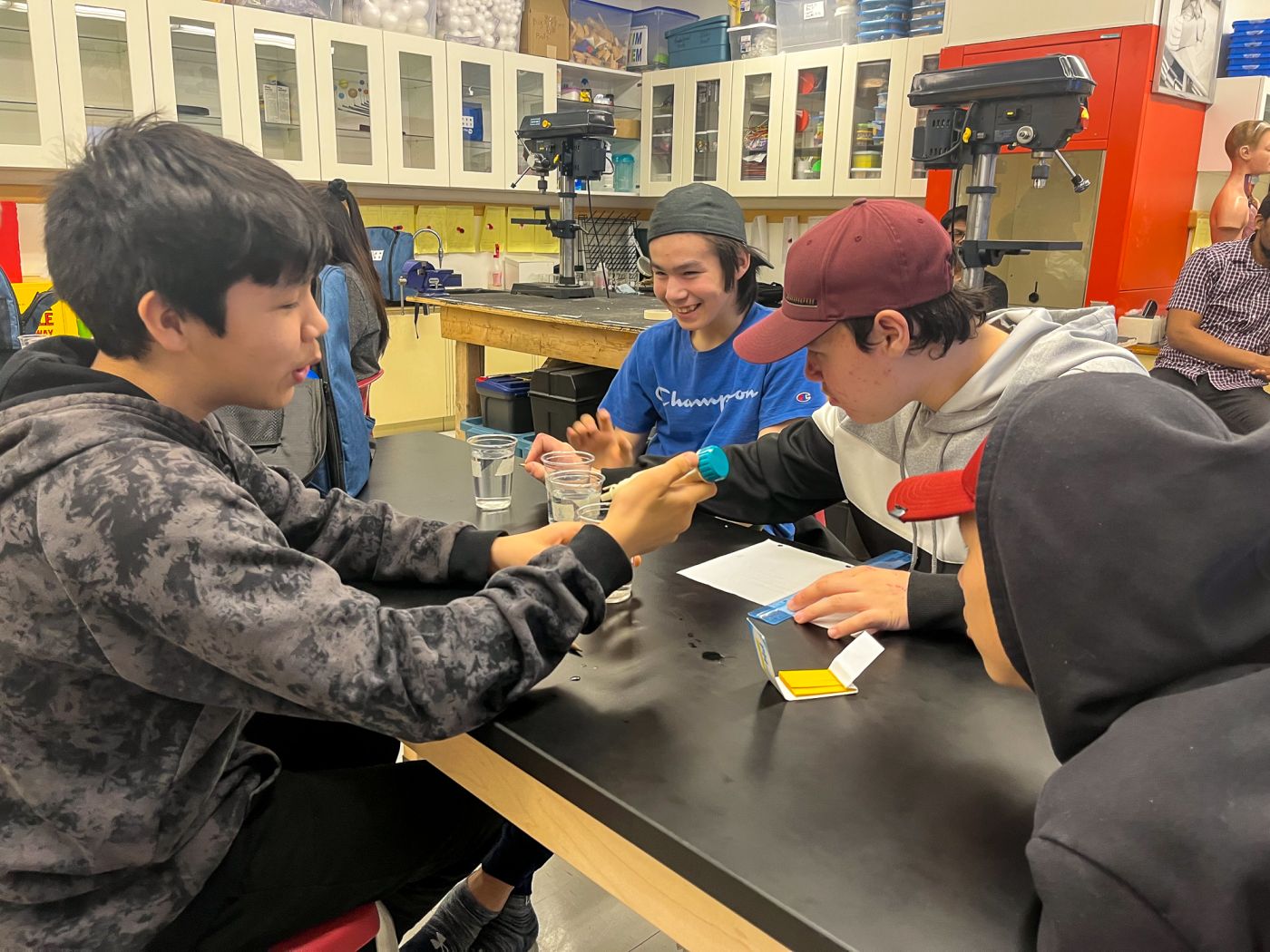

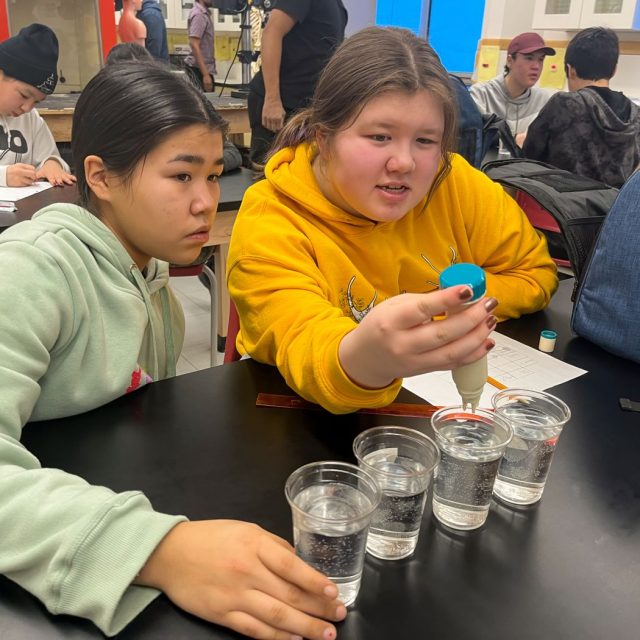

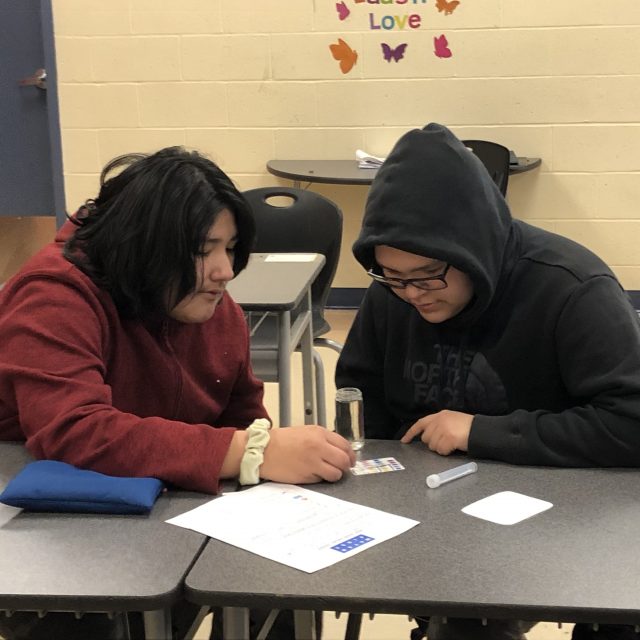

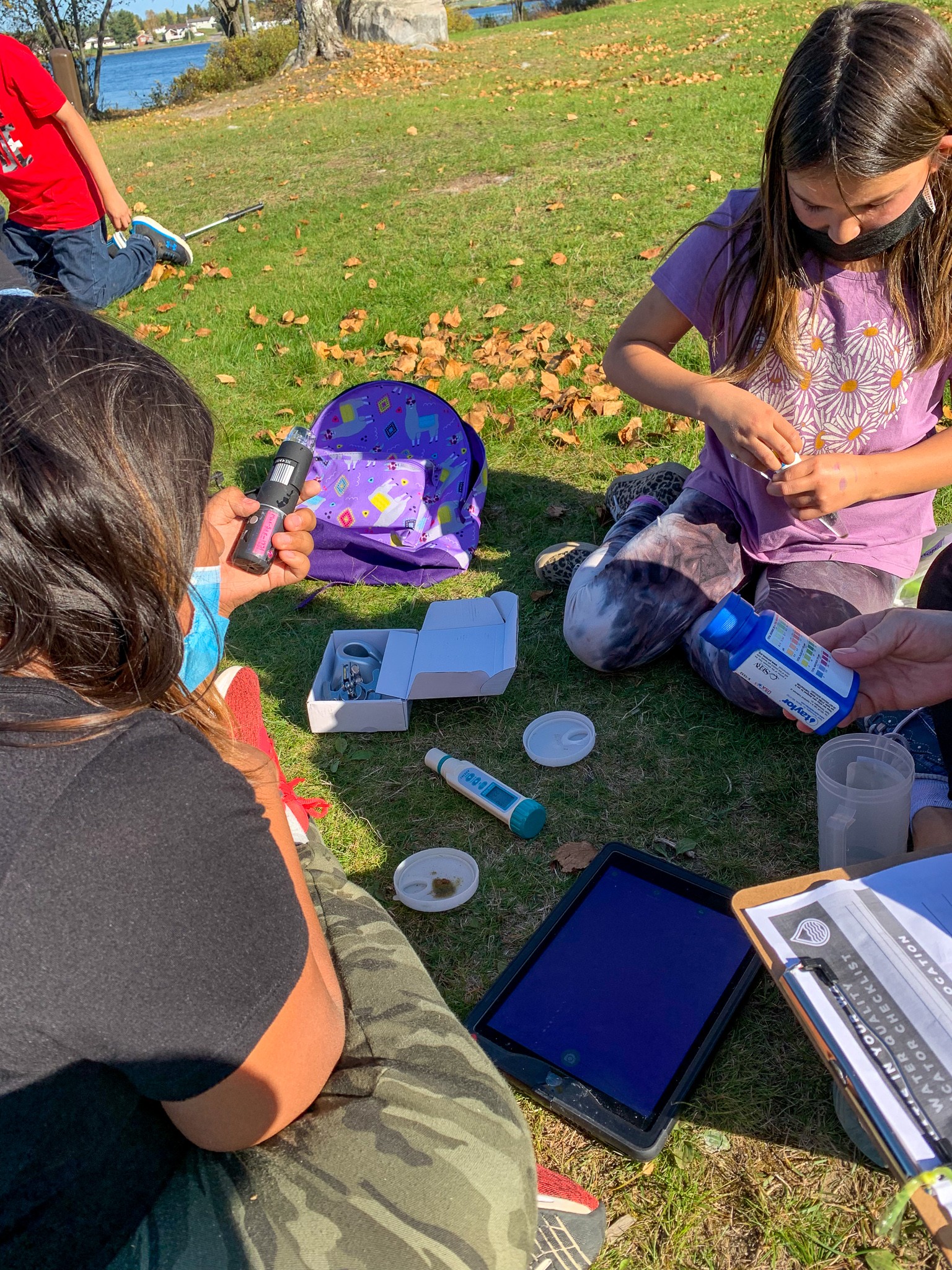

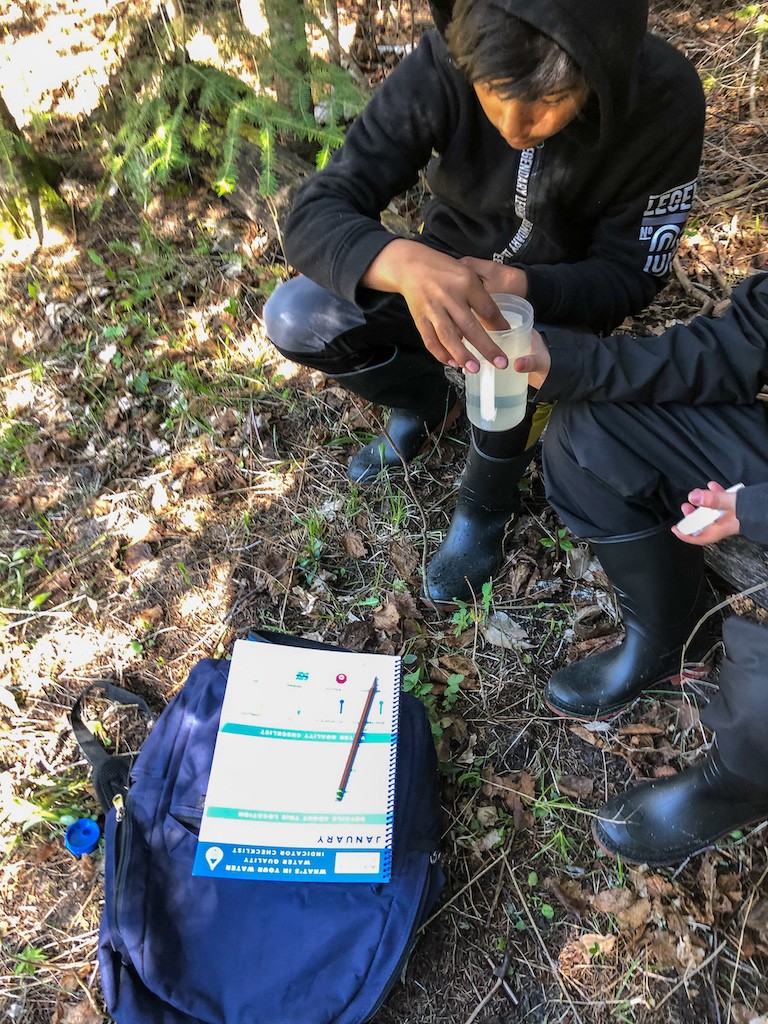

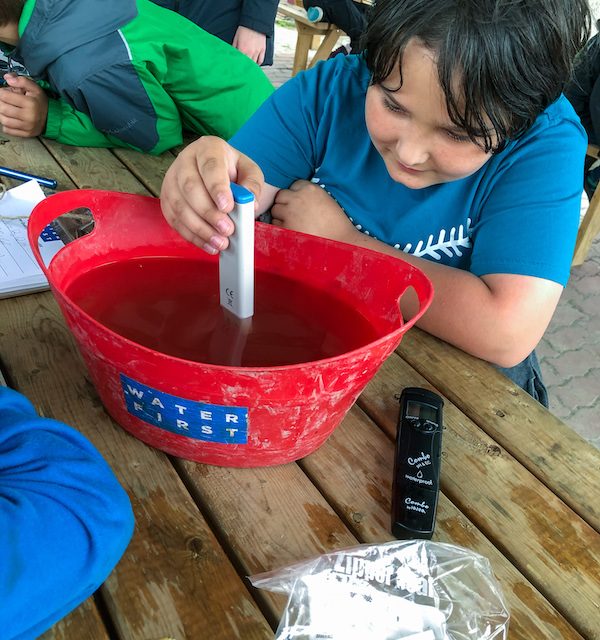

Measuring dissolved oxygen is always a favourite test during a workshop. After breaking off the tip of a glass tube, the magical (or scientific!) colour changing reveals your results!

The Water First gang posing with Taryn Meyers from CAWST at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology World Water Day Expo. Taryn hosted the panel that SJ (second from the left) had spoken on just hours before this photo. We all bought matching, hand-made bags from Disa Crow Chief, another incredible panelist at the event.

Speaking on a World Water Day panel alongside Disa Crow Chief and Nicole Newton, hosted by Taryn Meyers, our Director of Community Engagement, Sarah Jayne, tries her best not to look at her coworkers during the panel because we were all too proud of her, and our “encouraging eyes” would send her over the edge.

A bitter-sweet moment captured as we wrap up two amazing weeks in Alberta, arms weary from carrying the monitoring gear through one final snowy, uphill haul.