Partnerships in Action

2022 Annual Report

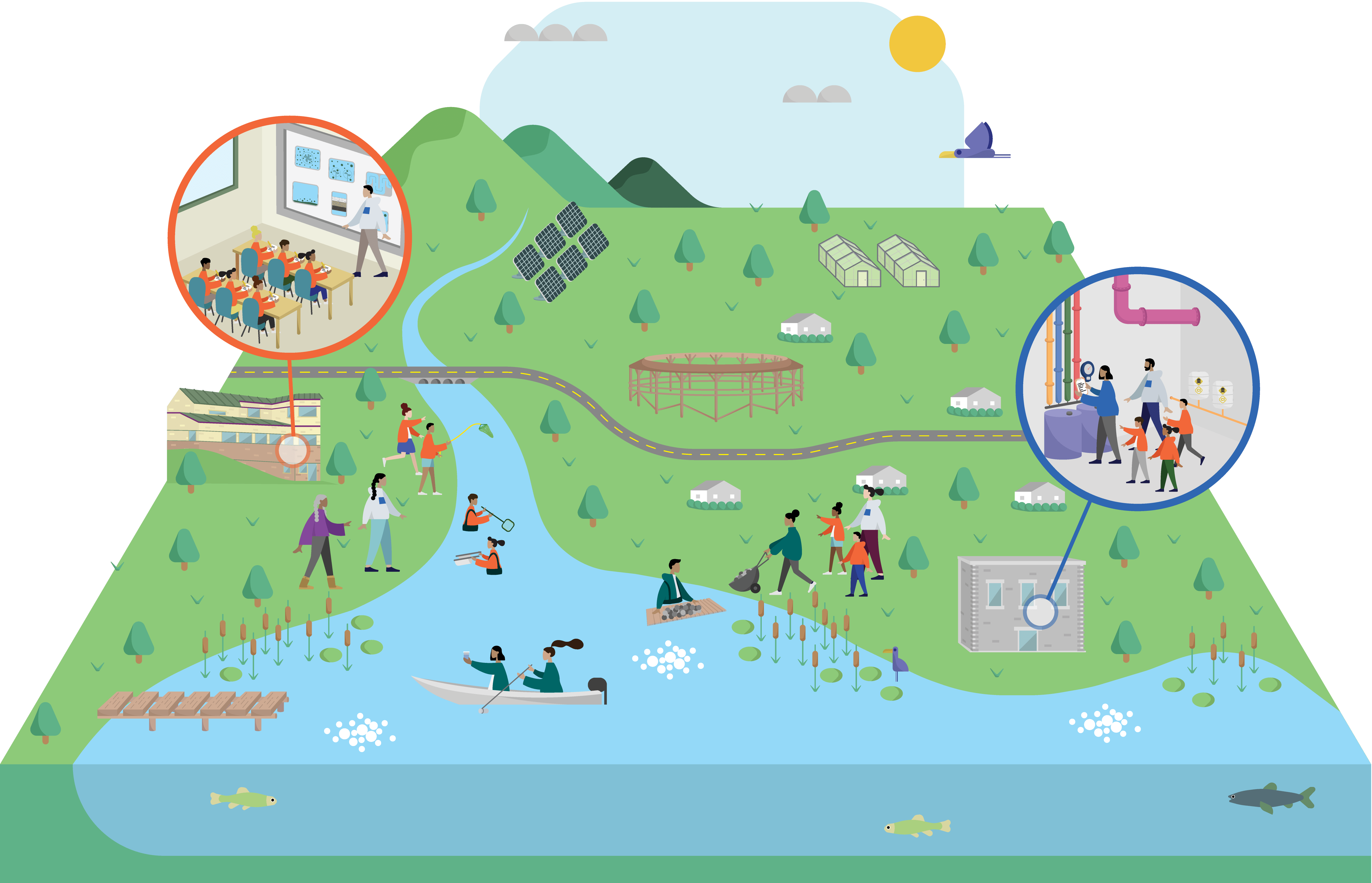

Partnerships for safe water and strong communities.

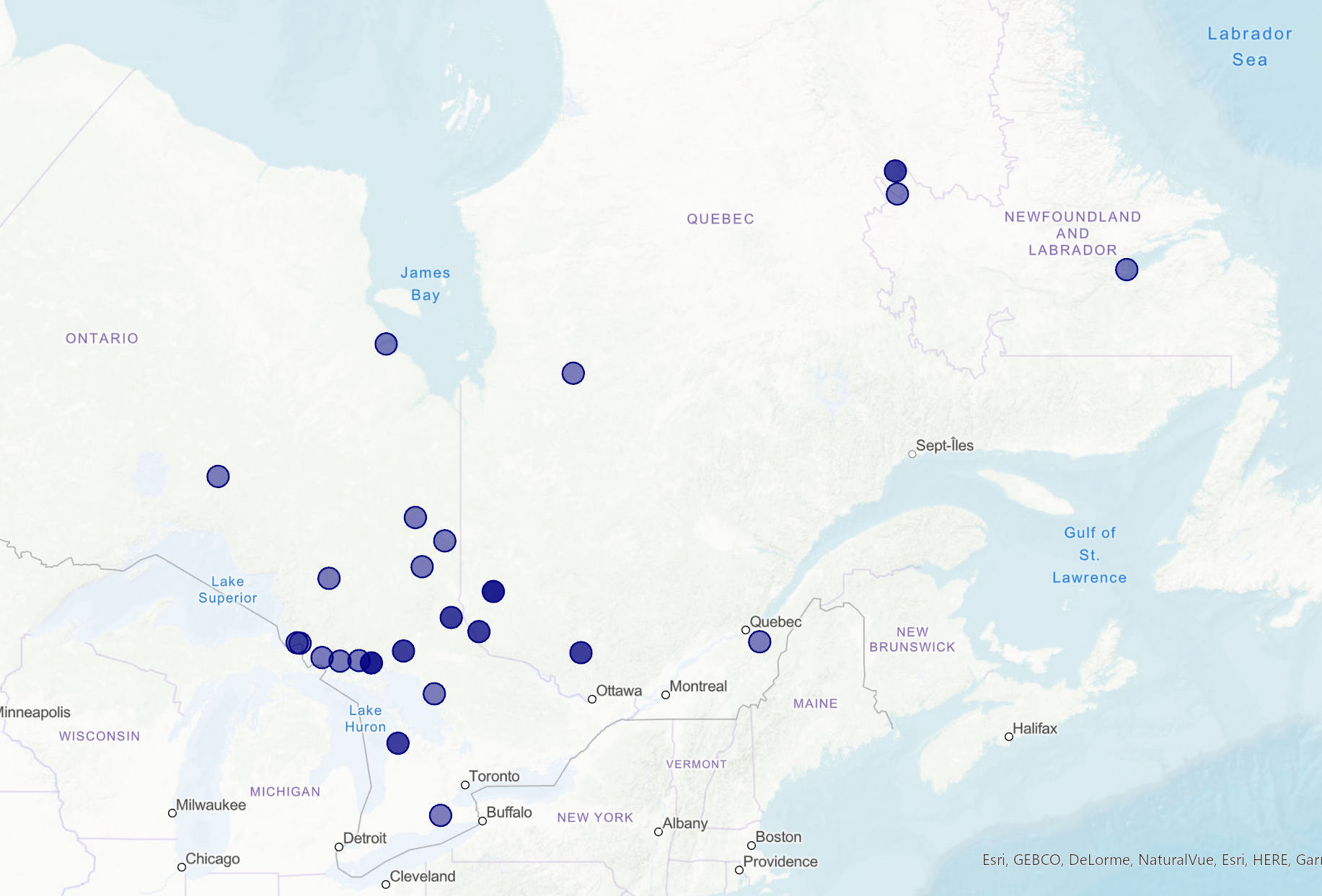

Sustainable access to safe, clean water in Indigenous communities continues to be a pressing need in Canada. As of July 2022, 111 First Nations communities* across the country are affected by drinking water advisories – that’s 18% of communities that are facing this critical challenge.

Water First Education & Training Inc. is a charitable organization partnering with Indigenous communities to help address local water challenges through education, training and meaningful collaboration. To date, we have collaborated with more than 65 communities to support the training of future water treatment plant operators and water resource technicians, and inspire a love of water science in youth.

Partnerships are at the heart of what we do. We work with community partners to identify their training needs and long-term water resource management goals. We then co-create interactive and learner-centred programs that strengthen a community’s capacity to help meet those goals and benefit the local community.

Together with all partners, including communities, donors, funders, staff, other organizations and individuals who share our goals, we are working towards safe water and strengthened communities. For now and for the long term.

*Note: this number does not include Métis or Inuit communities.

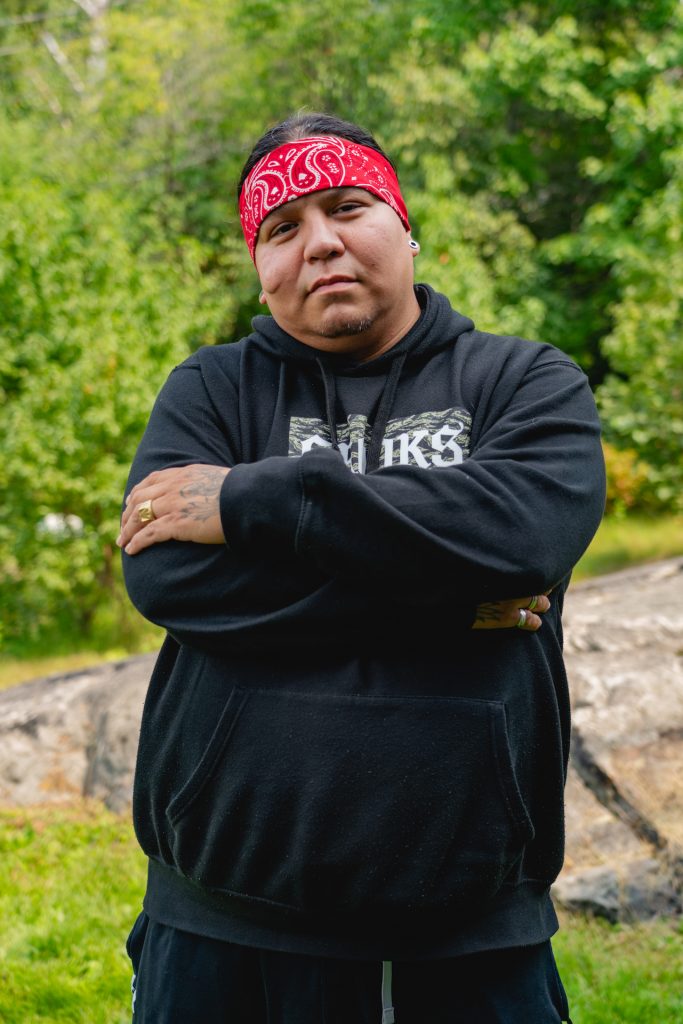

Ryan Osman. Brunswick House First Nation, Ontario.

Message from the Board of Directors

Water First has experienced consistent waves of healthy growth this year, in every way you can imagine.

Throughout this report, you’ll read incredible stories from some of the newest water treatment plant operators in First Nations communities. You’ll see the latest updates on fish habitat, water quality and climate change monitoring projects by Indigenous community members. You’ll get details on younger students’ outdoor experiential learning, which blends STEM* with water stewardship in collaboration with community Knowledge Keepers. The momentum of these co-creations is palpable.

The impact made this year, summarized on the pages to come, was enabled not only by Indigenous communities, but also by the people at Water First, who have created a strong culture of collaboration. A unique articulation of the values shared by the entire team was launched this year in a thoughtful and inclusive process, resulting in three interwoven Strands of Success. These strands illustrate the approach to every move the organization makes, and tell the story of how the strong, meaningful partnerships built at Water First are held together by interconnected relationships that flourish through mutual trust and the experience of long-lasting results.

We see these partnerships growing among the students and interns of the training programs, with community members, Tribal Council staff, and water treatment plant operators; with the Indigenous Advisory Council and amongst the Water First team and board. And, of course, with our donors and supporters, who get behind Indigenous communities in their work to develop local training and education as part of the solution to water challenges.

Reciprocal growth continues as the journey offers insight for everyone. As interns and students in communities learn, they, in turn, teach the Water First team just as much as Indigenous leaders do about their visions for their communities. Growth of the Water First team structure has also been a theme this year, with additional opportunities for new, brilliant and value-sharing talent to join the mission of Water First – in communities, in operations and on the board.

The co-creations happening at Water First are some of the most profound and innovative of our time. The work happening here sets an example for the way new generations can experience societies growing together.

*Science, technology, engineering, mathematics

The volunteer board of directors brings strong experience and advice in governance, engagement with Indigenous communities, communications, financial management, education and training, environmental sciences, entrepreneurship, and business best practices to the organization.

Leanne O'Brien

Board Chair

Indigenous Advisory Council

We work in a unique, ever-evolving and vast landscape. Naturally, there will be new opportunities, challenges and questions along the way. We look to partner communities and the Indigenous Advisory Council for insight, advice and guidance.

The Indigenous Advisory Council is composed of water treatment and environmental water specialists, educators, community leaders and Elders. The council provides guidance in the areas of program development, program delivery in Indigenous communities and community engagement.

When we engage with members of the council, they listen thoughtfully to weigh the new opportunities that are presented and understand the challenges we face. In return, they share tools and perspectives needed to approach these challenges and new opportunities. The guidance, trust and unwavering support that this relationship has been built on over years of working together is foundational to what Water First is today – and to our ongoing evolution.

Learn more about the Indigenous Advisory Council:

Indigenous peoples bring important teachings and knowledge to the table, based on thousands of years of successfully stewarding water resources on Turtle Island, while non-Indigenous people have brought western science and technologies that offer additional tools and knowledge. We need both. Protecting clean water is for everyone to do, and we’ll do it best together.”

Collaborative Decision-Making

Collaboration is at the heart of all decision-making. At all stages of our work – from the identification of community goals to the delivery of programming and beyond – we incorporate knowledge exchanges, feedback loops and evaluation points. This ensures the training and education needs of partner communities are met to the greatest potential and lasting results are achieved. This in turn keeps Water First accountable to the communities we partner with.

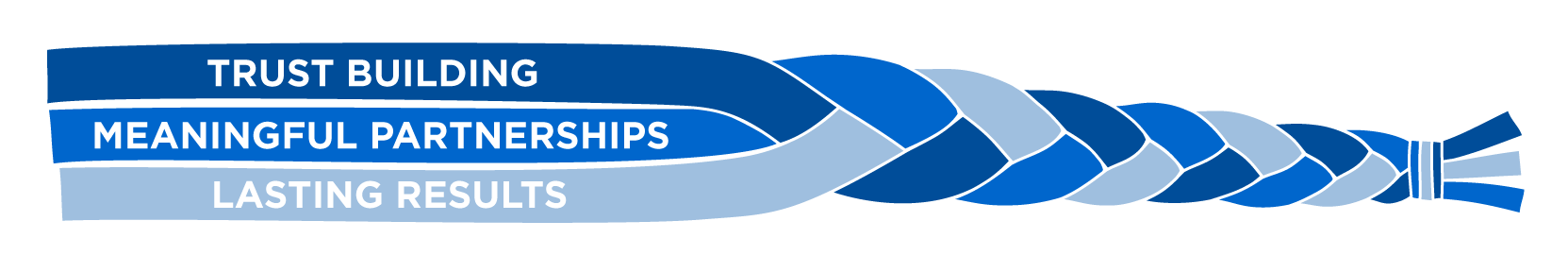

Strands of Success

The Strands of Success represent the essential qualities of Water First’s approach. Woven into the figure of a braid, the three Strands – Trust Building, Meaningful Partnerships and Lasting Results – express the ways in which we are intentional and make connections in everything we do.

Trust Building speaks to the respect, honesty, transparency, humility and integrity that are fundamental to our work with communities. These values are deeply held by our team. They act as the touchstone that grounds our engagements with community members, program participants, partners, supporters – and each other.

Meaningful Partnerships – the theme of this annual report – is the human side to what we do and why we do it. This Strand represents our full and sincere commitment to collaborations built on open communication, mutual knowledge exchanges and common goals. And those collaborations and connections happen along multiple planes at Water First. Staff are invested in developing strong partnerships with one another, so we can leverage our unique skills and passions for fruitful results. We focus on nurturing partnerships with donors so everyone can feel invested in our shared successes. In addition, Water First’s relationships with our volunteer board of directors, the Indigenous Advisory Council and other champions are crucial for guidance, feedback, innovation and thoughtful action.

Lasting Results reflects how we strive for sustainable outcomes, with benefits remaining within Indigenous communities for the long term. The work Indigenous communities are doing to solve the water crisis will take time. The impact and support from Water First engagements must have longevity.

Foremost to Water First’s work are the respectful, reciprocal, and meaningful partnerships we develop with Indigenous community members and program participants. Together, we create and sustain a rich and fertile space where knowledge, understanding, and sustainable solutions can thrive.

Read more about our Strands of Success:

Nathan Copenace from Washagamis Bay First Nation, a graduate of the Drinking Water Internship Program with Bimose Tribal Council in Northwestern Ontario and Jag Saini, Project Manager at Water First. Nathan was the valedictorian of his class and is now working as a water treatment plant operator in his home community, which recently came off a boil water advisory that had lasted for over a decade. Watch this video to learn more from Nathan.

Our Impact in 2021-2022

Investing in Scalability for Long Term Impact

Water First has taken steps to ensure our high-quality and high-impact education and training programs are able to scale so we can meet the needs of any community wishing to partner with us. We acknowledge the need to invest more time and resources into strengthening the framework that allows us to deliver our programs and respond to increasing community interest.

Water First must scale up in a way that is smart and well managed, without losing sight of our focus on trust and meaningful relationships. This means growing well: investing in people through relevant training and attracting top talent; and strengthening resources and systems to provide vital equipment coordination, distribution and storage to support partnerships. This mindful and intentional approach will help us build capacity, while continuing to collaborate in a meaningful way and putting the needs of the communities first.

To date, Water First has collaborated with:

Indigenous

communities across

the country on...

co-created water

science training and

education projects.

Graduates of the

Internship

Program to

date, as of October 2022

Certifications achieved

this year through the

Internship Program

Hours of training this year: Drinking

Water Internship and Environmental

Water Program combined

Participants in

Environmental Water

projects this year

Collaborative

Environmental Water

projects this year

Workshops

delivered to school-

aged Indigenous

youth this year

Students engaged

through the

Schools Program

this year

High school credits earned

this year through the

Schools Program’s Reach

Ahead Program

*Note: Numbers for this year reflect Water First’s fiscal year of September 2021 to August 2022.

Our Programs

Intern to Operator with the Drinking Water Internship Program

In many communities, existing water treatment staff are doing a great job with available resources. However, communities have identified the need for more qualified local personnel to support solving water challenges.

The Internship Program supports young Indigenous adults to become certified water treatment plant operators. This in-depth training program addresses community-identified needs, supports building local capacity, and helps to ensures sustainable access to safe drinking water in Indigenous communities for the long term.

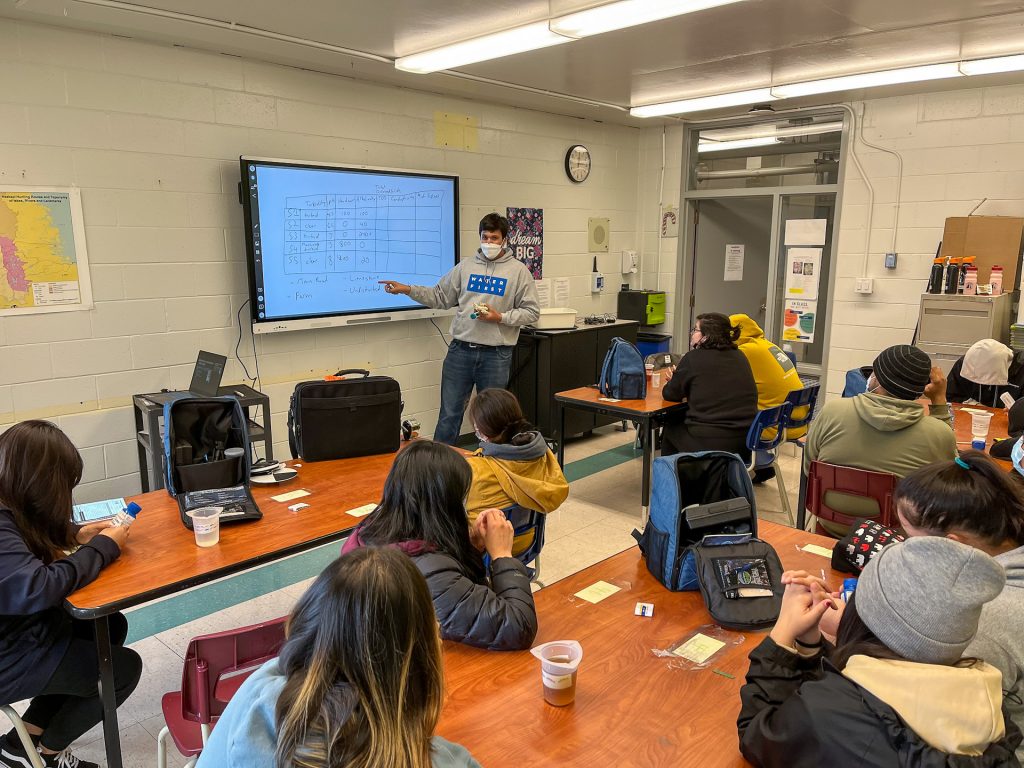

During this paid 15-month program, interns receive over 2,000 hours of hands-on skills training and experience — in the classroom, at local water treatment facilities and out on the land. This training helps the interns obtain four provincially recognized certifications.

Designed to build relationships and overcome barriers together

Building the knowledge and skills required to become a certified water treatment plant operator is the main objective of the Drinking Water Internship Program. However, the program is customized to the base of knowledge and experience each intern brings with them. This approach is unique, and requires dedication, effort and building trust with each intern.

This learner-centered approach includes constant evaluation to determine how the program could better support the interns. A feedback loop with current interns is encouraged and constant. We need the input to know how they are thriving and where they are challenged. And they do share this input — for themselves and for future interns. This takes a deep level of trust that is carefully built over time.

So, when the results from the first sitting of the Water Quality Analyst exam, one of the three certification exams the interns challenge, was largely unsuccessful, we worked hard with the interns to identify the barriers to success.

Through feedback from the interns, observation and discussion, it became clear that there was a lack of experience with in-depth water chemistry theory, lab equipment and experimental techniques. This was understandable. When compared to larger water treatment facilities, the smaller water treatment plants that the interns work in do not usually complete as much lab analysis in-house. Currently, the interns don’t get as much practice with these valuable concepts and techniques during their work placement.

However, even though they may not use the skills currently, expanding the in-house capacity creates opportunities to be able to do so in the future.

To support overcoming this barrier, an entirely new training week was added to the program. The new week-long workshop was designed to focus solely on building foundational knowledge of water chemistry theory, lab equipment and technical lab skills through a collection of hands-on activities and lab experiments. Since the interns couldn’t go to a lab, the lab came to them.

A successful learning environment requires trust and meaningful relationships; between trainers and interns, and also between interns. By keeping these values always in our focus, they are ingrained in what we do. Not an afterthought or a surprise when it happens, but intentional and integrated as an objective to support building relationships.

Learn more about the Drinking Water Internship Program:

Paige Manitowabi, a graduate of the pilot Drinking Water Internship program on Manitoulin Island, went on to be employed by Waabnoong Bemjiwang Association of First Nations as the Local Internship Coordinator for the Georgian Bay Internship. In addition to her coordination work, she developed and piloted a Traditional Ecological Knowledge workshop for the Georgian Bay interns.

Hunter Edison is a graduate of the Drinking Water Internship Program with Bimose Tribal Council and is now employed as the lead operator at his community’s water treatment plant.

In a recent video, Hunter shares the story of how he took a leadership role in providing his community with safe, clean water in the face of an emergency.

In March of 2022, Nick Chapman, a graduate of the Drinking Water Internship Program, wrote a beautiful reflection on her experience in the program at that time: what she has learned, the certifications she has gained, and how Water First has supported her along the way.

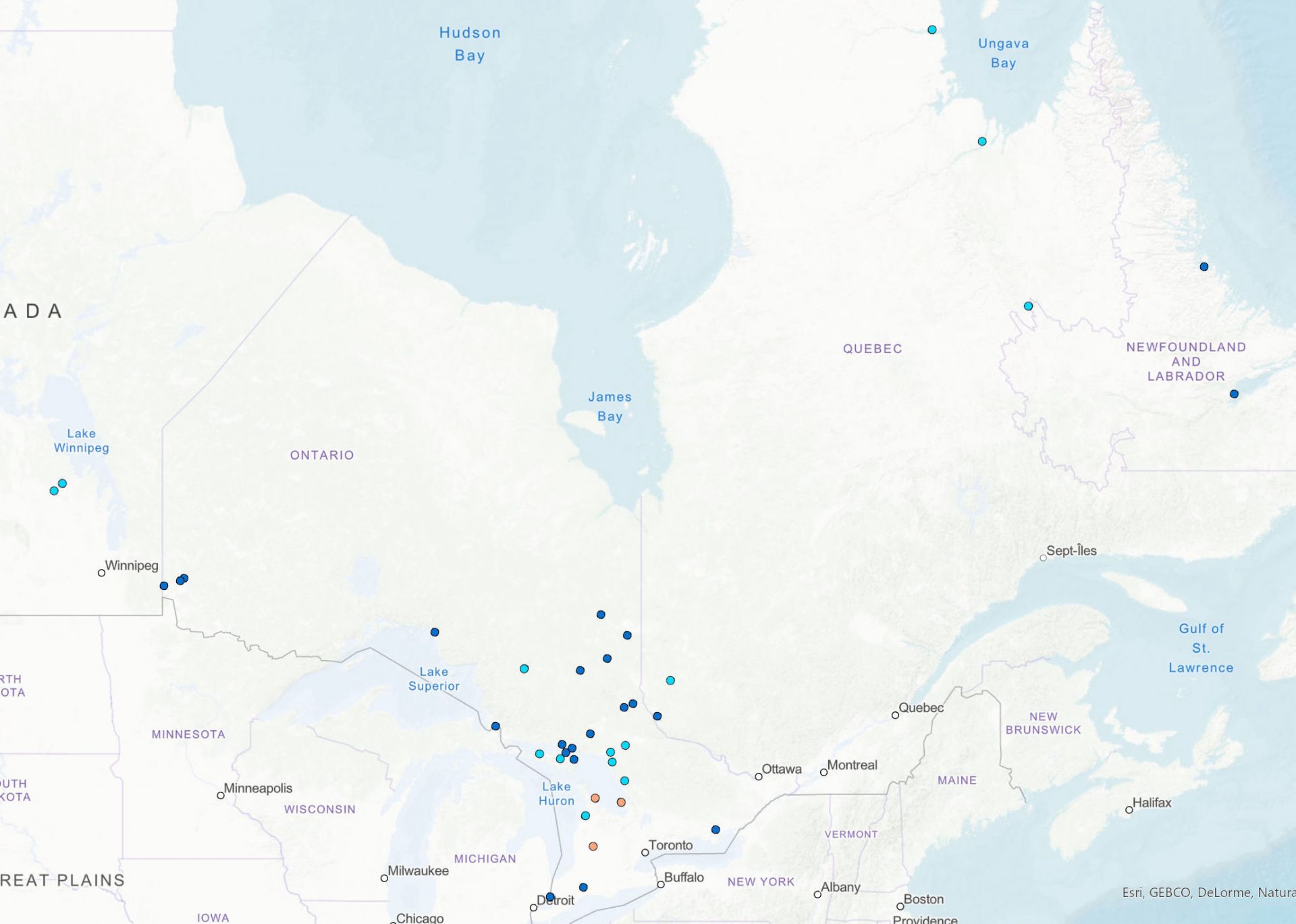

Project-based technical skills training to meet community goals

Time and again we have heard from communities about goals to strengthen their capacity to manage aquatic resources and monitor climate change. The Environmental Water Program provides technical training in fish habitat restoration, water quality monitoring, mapping and data management. There is a high demand for this type of training. What sets us apart is our approach.

We consult with Indigenous partners about current challenges and long-term environmental water goals to determine priority areas and local training needs. Then, we customize project-based training programs to support the community to meet their needs and goals. Project-based training provides a way to learn and directly apply new knowledge and skills out on the water. The long-term goals of the community inform and guide the project that is carried out.

The ultimate result is a project completed for a community and by a community, which brings invaluable experience and increased confidence through the process.

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach

In 2018, we began our first long-term environmental project with the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach. This first project was a study of fish populations and contaminants (including mercury) in several popular fishing lakes in the region. Subsequent projects have focused on fish population surveys, as well as fish habitat mapping and restoration, which will continue our work together for years to come.

Each project is run by community members learning to carry out the projects along the way with the support of Water First technical staff. Interns that have been involved since 2018 are now taking a leadership role in helping to train newer interns.

Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation

In the summer of 2021, the Environmental Water Program team began a new project in collaboration with Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation (SIFN) in Labrador. SIFN is investing in long-term climate change monitoring with a focus on creating a water management system and on fish habitat monitoring.

These projects will support their efforts to restore a lodge on Iatuekapau (Park Lake) in central Labrador to be a 100% Innu owned-and-operated adventure tourism and education facility.

In 2019, Saugeen Ojibway Nation

began their Coastal Waters Monitoring Program (CWMP). Recently, the community approached Water First to design and deliver customized training workshops to help enhance the technicians’ understanding of the sampling methods, data collection, resource management, GIS mapping, and climate adaptation and monitoring.

Learning and innovation in an

environment of trust

On the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula, just south of Wiarton, Ontario, stands a building that was once a car mechanic garage. Behind the large roller doors is the office of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON) Coastal Waters Monitoring Program (CWMP). Lining the walls of the large garage are boxes of sampling bottles, fish sampling gear, water testing chemicals and wetsuits hung to dry. A large boat covered with a tarp is visible through a side doorway, awaiting the team’s next water sampling adventure.

Skilled and experienced technicians from SON are working for the Environment Office of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation running the CWMP. Along the shores of the Saugeen Peninsula, water quality and fish population data has been collected over the last four years. Emily Mansur, one of the technicians, met Kendra Driscoll, Water First’s Water Quality Specialist, at a conference. She asked if Water First could provide four weeks of training workshops on water quality monitoring, GIS and mapping, fish conservation and climate change monitoring.

In preparation for the first workshop, the team described what was currently being measured and how the operations of the CWMP project was running. We listened intently to understand the baseline knowledge and identify learning goals that would best support this ongoing monitoring program.

Specifically, they were looking for support in understanding what all the data means. For example, how is all the information that is being collected connected to the health of the water? What does the information collectively say about the fish populations in the area? How can the data being collected better support the protection of the water and land of their territory?

What was striking was the honesty and openness about what the team knew and what they wanted to learn. This takes vulnerability and trust that we would handle their gift respectfully.

To date, two workshops have been delivered, and planning is in process for the last two workshops set for 2023. Together, we have started on a path towards a meaningful partnership that will provide tools for the technicians to take the CWMP program from where it is today to their vision of tomorrow.

Read more about our Environmental Water Program:

Inspiring future water scientists with the Indigenous Schools Water Program

Certified educators at Water First have developed comprehensive programs that create opportunities for students to strengthen their relationship with the environment, and to foster a love of water science.

Our programs, designed for kindergarten to Grade 12 students, include multiple week-long, hands-on STEM workshops that explore custom curricular and local water science concepts. Students spend time on the land and in the classroom exploring these topics using water science tools and Water First learning resources. Working in collaboration with community members, students gain a comprehensive understanding of their local geography and watershed. They also learn about the role they can play, as students and as young professionals, in protecting their water resources.

Photo: Jennifer MacDonald. Long Point First Nation, Ontario.

Reaching ahead through enriching, hands-on, applied school programming

In the summer of 2021, an eight-week outdoor experiential learning program was piloted with nine Grade 8 students of Beausoleil First Nation, who earned Grade 9 Geography Reach Ahead credits. This was delivered as part of Water First’s Indigenous Schools Water Program.

Through land-based activities that related to the geography curriculum, the students earned their credits while participating in Beausoleil First Nation’s Wind and Water Monitoring Project, collecting water samples and reporting E. coli levels on six local beaches — the first collaboration of its kind within Water First programming.

With the support of local environmental science professionals, Water First instructors incorporated the ongoing monitoring project to support the students in their learning and data collection. What students learned from the local professionals made the program place-based and culturally relevant, and strengthened their connection to their community.

After such a successful pilot, the depth and enriching experience of the Reach Ahead Program is creating a wave of interest and momentum. The program was delivered in the summer of 2022 with 17 new students in Beausoleil First Nation, as well as 12 students from Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation and Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation.

In your own words: Sharing knowledge through local language

In late May 2022, Kabimbetas (Noah) Mokoush stood with students from Jimmy Sandy Memorial School in Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach. Speaking in Naskapi, Kabimbetas began to explain the concept of a watershed to the students. Hearing the explanation in their own language, several students nodded, captivated, as they listened.

The high school students from Grades 9-11 were participating in one of four week-long STEM-based workshops with Dillon Koopmans, Senior Manager of our Schools Program. The workshop’s focus was on water quality and watershed stewardship.

Students learned to run their own small-scale water quality monitoring programs in our Model Watershed activity. They also learned how to interpret water quality data to identify sources of water pollution in the Watershed Mysteries activity. When Kabimbetas was invited to share his knowledge and experiences with the students, he agreed.

As a long-standing Environmental Water Program intern and a research associate on several projects in Naskapi territory, Kabimbetas drew on years of experience to share his understanding of watershed stewardship. He demonstrated to the students how he uses water quality monitoring tools with Water First, and described his work on the fish population and contaminants studies in Naskapi territory from 2018-2020. Hearing the concepts in their own language and connected to their local context helped the students grasp how watersheds work.

While Kabimbetas was teaching the students, Dillon and Keegan Smith, Water First Technical Trainer and Project Coordinator, could feel the spark he was striking in the class. The students were engaged, attentive and curious as these concepts were explained in their language. It was so exciting to watch Kabimbetas pass his learning directly to the students, building their knowledge and capacity from his own.

Our Schools Program workshops aim to show students the possibilities of water science. Workshops like these lay the foundation for a future they can see themselves in. For the students, Kabimbetas’ presence and stories of his work have an impact beyond the day’s lesson. As a community member and an experienced intern, Kabimbetas is a concrete example for the students that working as a water scientist is a tangible, viable future. He is living proof of the importance of the work benefiting their community with long-lasting, far-reaching impact.

The meaningfulness of this experience with Kabimbetas contributing to the students’ experience was truly a culminating moment for the strong partnership between Water First and Naskapi Nation.

Our partnership with the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach began in 2018, working together on community-led environmental projects in fish habitat restoration and fish contamination studies. Since January 2020, the School Programs has delivered STEM-based programming to over 100 students of Naskapi Nation.

Read more about our Indigenous Schools Water Program:

Nuturing Interconnectivity

Collaboration with community partners is foundational to our work. This year, it became strikingly evident how interconnecting program areas deepen the experience and thus the impact for participants, communities and staff alike. When students and interns get to work together, it is exciting to observe the sparks that emanate from them. Through these experiences, students learn about the role they can play, as emerging scientists, in protecting their water resources. Interns learn that their work has an impact beyond the treatment plant processes they are learning, the water quality parameters they are tracking or the shoals they are restoring. Communities, with a widening web of knowledge and capacity, benefit from further reaching impacts.

These experiences are equally enriching for the team at Water First. It is our privilege to witness the light and connection that participants bring to their programs, and we are all fortunate to have the opportunity to continuously collaborate and learn from each other.

In the summer of 2022, seven Water First Environmental and Drinking Water Program interns from six Indigenous communities, along with Water First staff, achieved their CABIN (Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network) certificate. Being together for a week in Long Point First Nation allowed for plenty of time to share local food, chat about differences in languages, learn about each other’s experience in different Water First programs, and ultimately connect more deeply with other Indigenous leaders in water sciences.

While delivering programming to students in two Innu communities in Labrador, Sheshatshit and Natuashish, the Schools Program team was joined by Seth Hurley, an Environmental intern working with Water First on a climate change and fish habitat monitoring project at Iatuekapau (Park Lake). During his visit, Seth demonstrated to the youth some of the tools being used in the Park Lake project, speaking in both Innu and English to better accommodate the students.

In July 2022, when the North Shore Tribal Council Drinking Water Internship began, Nathan Copenace, a graduate of the Internship Program, and Terrence Fortin, a current intern, joined the group to share their experiences as interns. The new interns were able to ask questions and hear first-hand accounts. Nathan and Terrence expressed how the Internship was the best thing that ever happened to them, reassuring the new interns that this endeavour was full of opportunities for success.

When the Schools Program team was in Dokis First Nation, south of Lake Nipissing, students at Kikendawt Kinoomaadii Gamig went to visit the local water treatment plant. Working there were two Drinking Water interns, Kennedy Dokis and Harmony Restoule. Seeing community members working to provide clean water, students are able to deepen their connection to what they are learning about in our workshops and can see for themselves a career path that water science can lead to.

Financials

Meaningful collaboration and respectful relationships with Indigenous communities have been the catalyst for developing relevant and sustainable solutions. This is only possible with the support of donors who invest in our approach to education and training.

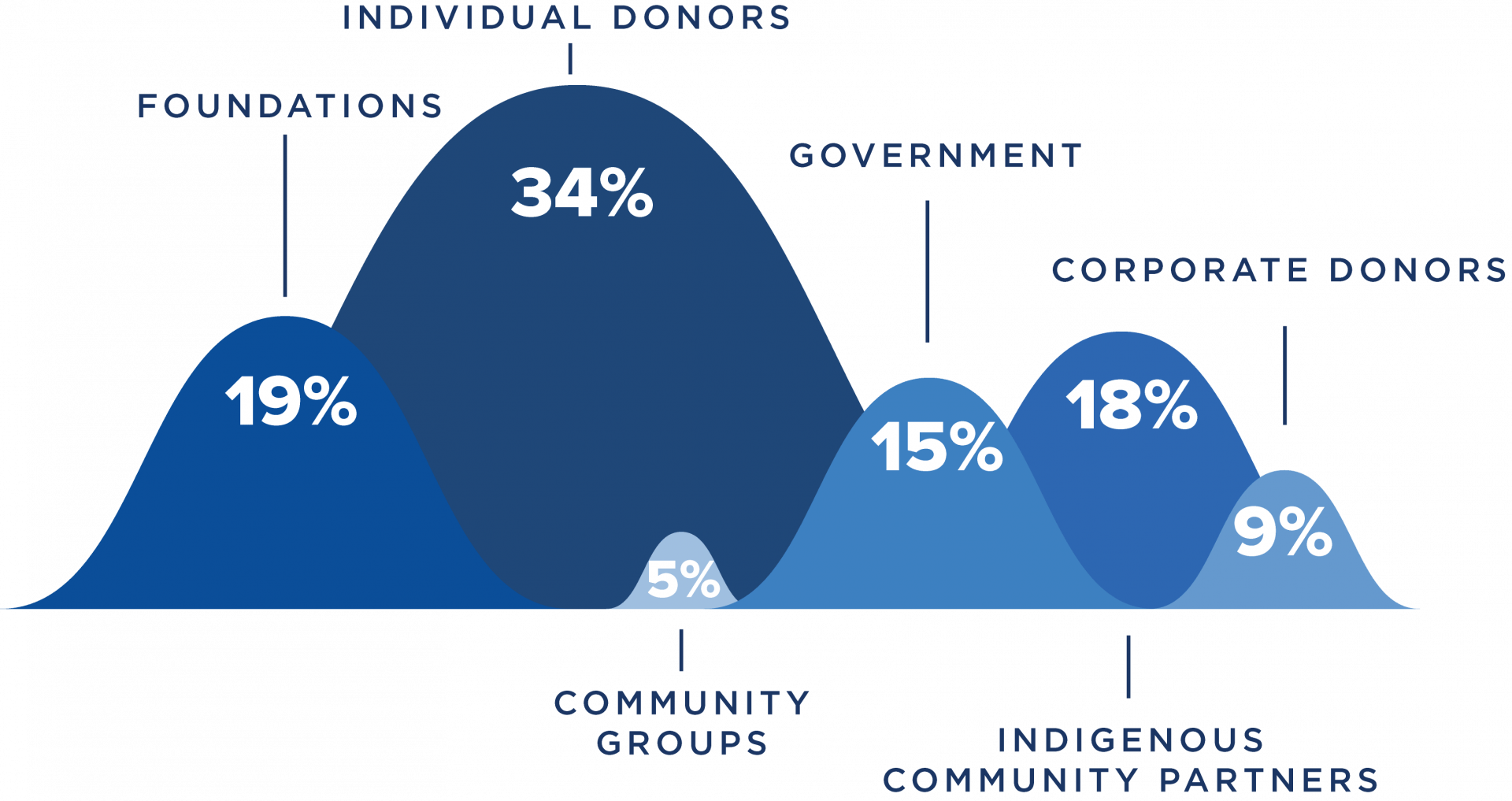

Expenditures

Revenue

Note: Audited financials are for the 2020-2021 fiscal year. 2021-2022 audited financial statements will be available in spring 2023.

Water First has been rated 5 Stars by Charity Intelligence (Ci), an organization that conducts assessments of charitable organizations to promote transparency, accountability and a focus on results in the charitable sector. Ci’s rating is based on financial transparency, results reporting, demonstrated impact, need for funding, and cents to the cause.

Water First has been rated 5 Stars by Charity Intelligence (Ci), an organization that conducts assessments of charitable organizations to promote transparency, accountability and a focus on results in the charitable sector. Ci’s rating is based on financial transparency, results reporting, demonstrated impact, need for funding, and cents to the cause.

The Community Based Walleye Spawning Habitat Restoration Project is a collaboration between Water First and Long Point First Nation (LPFN) to enhance walleye spawning habitat near the community of Winneway, in the Abitibi-Temiscamingue region of Quebec. Two sites have been selected based on current use as spawning habitat, their need for improvement, and proximity to the community for use and monitoring.